Smuggling in and around Burton Bradstock

The history of Burton Bradstock could not be written without reference to its illegal seafaring association. There are many legends of the activities of smugglers operating in the area, as Burton Bradstock was a key landing place at the centre of Lyme Bay. According to experts in the 19th century, "if there was any smuggling at all in south-west Dorset, the preventive officers could be sure to find it at Burton Bradstock for this had long been a noted contraband centre and official fears of a great revival in the trade there after the peace in 1815 were well-judged. Here and at Swyre, two or three miles to the east, the Northovers had a finger in every tub and provided regular employment for the keeper of Dorchester Gaol" (more about the Northovers later).

The following material is largely taken from an excellent book by Roger

Guttridge entitled 'Dorset Smugglers' and published by Dorset Publishing

Company - sadly now out of print (see Books & Publications). We are very

grateful to Roger Guttridge for giving us permission to use his book.

There are two schools of thought on the rights and wrongs of smuggling, and two strikingly different definitions of a smuggler. Samuel Johnson described him as "a wretch who, in defiance of justice and the laws, imports or exports goods either contraband or without payment of the customs".

Whereas Adam Smith, the eighteenth century economist and advocate of free trade, was more generous: "The smuggler," he wrote, "is a person who, though no doubt blameable for violating the laws of his country, is frequently incapable of violating those of natural justice, and would have been in every respect an excellent citizen had not the laws of his country made that a crime which nature never meant to be so."

Picture

by G Morland

Picture

by G Morland

Few smugglers felt the need, or possessed the eloquence, to intellectualise about the morality of their trade but those who did used much the same arguments as Smith: the goods which they smuggled had been honestly bought and paid for, were transported at their own expense and were demanded by a wide cross-section of the public who, in many cases, could not otherwise have afforded to buy them. Adam Smith was reflecting not only the viewpoint of a select group of free-trade economists, but an ancient and deep-rooted national conviction that smuggling - the evasion of prohibitions or duties - was not truly a crime but rather a justified defence of people's rights to buy and sell as they chose, without interference from officialdom. As the infamous Hawkhurst Gang said when they broke into Poole Custom House to retrieve a cargo which had been seized: "We come for our own and will have it."

It was an attitude which survived to modern times and which is now manifest in the evasion of income tax; a twentieth century official who "cheats" people out of one-third of their hard-earned cash is regarded by many as fair game for a little cheating in the other direction. In the same way, the collectors of customs in earlier times were widely regarded as legalised robbers who, at the very least, deserved a little of their own medicine.

Inevitably though, smuggling, by its very nature as well as its profits, attracted the worst elements of society. Law-breakers of all kinds were among the first to jump on the contraband wagon, encouraged by the public support which smuggling attracted as well as by the prospects of adventure and financial gain. The presence of ruthless villains and ruffians in the gangs led, in turn, to violent clashes between smugglers and Revenue men and turned the cliffs and coasts of England's otherwise fairly quiet land into a blood-soaked battleground comparable with the Wild West of pre-industrial America.

The history of smuggling in England goes hand in hand with the history of the Customs institution. The latter dates from Saxon times when King Ethelred II imposed a toll charge, or import duty, on boatloads of foreign wine arriving at Billingsgate. Thereafter it became a "custom" for foreign vintners to give up a portion of their cargoes in return for permission to trade - hence the origin of the term. Such tolls, however, applied only to certain ports, so evasion was neither difficult nor illegal.

And the word "smuggle" itself probably dates from this period. Though primarily from the Scandinavian languages - the Danish smugle which literally means "smuggle" and the Swedish smuga means "a lurking hole" - the Anglo-Saxon smugan, "to creep", is probably cognate with the Icelandic prefix smug which stems from smjuga, and means "to creep" or "to creep through a hole".

It was not until the last quarter of the thirteenth century that the gauntlet which inspired England's first true smugglers was tossed in their path: in 1275, King Edward I, seeking new sources of revenue, introduced a custom on wool exports. Wool was a mainstay of the national economy and was in great demand on the continent. To collect the duties, a permanent Customs staff was established and almost immediately the first smugglers appeared. These were known as "owlers" because their operations were largely nocturnal.

As the years passed, the economic needs of monarchs increased and duties were accordingly raised or extended to other commodities; each time this happened new opportunities were presented to smugglers and another stone was laid on the foundations of the great smuggling age.

Life for the early generations of smugglers was comparatively easy. It was not until the fourteenth century that the first revenue cruisers appeared in coastal waters and even then their areas of patrol were limited to ports and estuaries; for the determined smuggler, long stretches of coastline remained totally unguarded. Many, however, did not consider such diversions necessary, preferring simply to bribe the Customs officers in the ports. This was not difficult. Corruption was widespread in society generally, Customs men were poorly paid and the presence of an honest officer in a port was more exceptional than normal.

One notable exception was the searcher at Poole in the mid-fifteenth century, William Lowe. He had an enormous coastal area to cover and only a horse for transport: his district stretched from West Dorset through Hampshire to Sussex, but he performed his duties with dedication and vigour and is one of the most conscientious Customs officials on record. Countless cargoes of wool and leather fell prey to his ubiquitous talons and in 1452 he seized a Dutch ship stacked high with vast quantities of goods which fifteen merchants from Sherborne, Bridport and Charminster were trying to smuggle out of the country. Lowe came to be despised by merchant smugglers and the following year was attacked by a London wool merchant, who "smote me with a dagger in the nose, and through the nose into the mouth". Lowe survived not only to tell the tale but to write a report on the incident in his own hand.

A further encouragement to the smuggler was the public support his business attracted and the favourable consideration he could expect if tried by a jury. Such was the official concern over the bias of juries that when John Roger of Melcombe Regis, a suspected wool smuggler, asked for a trial rather than pay a fine in 1428, the Privy Council refused his request on the grounds that a local jury was likely to acquit regardless of the evidence. Instead they fixed his fine at two hundred marks "or more if he can afford it"!

Smuggling since 1700:

1700's - Smuggling gets out of hand!

A vivid picture of how developments affected Dorset survives in the correspondence of Philip Taylor, who was Collector of Customs at Weymouth from 1716 until some time in the 1720's:

During the winter of 1717-18 he wrote: "the running of great quantities of goods having of late very much increased" - the government tried to push through a bill for the prevention of smuggling. It fell down in the House of Lords and, as a result, reported Philip Taylor the following April, "the smuggling trade is prodigiously increased and they and all persons concerned with them are become more insolent than ever and dares any power to oppose them, which will very soon have a very bad influence on trade. Besides, as these smugglers are generally the dissatisfied part of the country, their riding in troops of thirty or forty armed men on the least appearance of an opportunity will be dangerous to the peace of the country as well as troublesome to the Government." The smugglers even had the audacity to claim - and they used the failure of the smuggling bill as their evidence, that they were now "tolerated in smuggling by the King, Lords and Commons."

The bill, - which, among other things, forbade the importation of cargoes in vessels of under fifty tons - finally became law twelve months later, but by then Taylor was writing in colourful style:

"The smuggling traders in these parts are grown to such a head that they bid defiance to all law and government. They come very often in gangs of sixty to one hundred men to the shore in disguise armed with swords, pistols, blunderbusses, carbines and quarterstaffs; and not only carry off the goods they land in defiance of officers, but beat, knock down and abuse whoever they meet in their way; so that travelling by night near the coast, and the peace of the country, are become very precarious; and if an effectual law be not speedily passed, nothing but a military force can support the officers in the discharge of duties."

The contraband boom continued, reaching a level in 1719 which would have been unimaginable five years earlier. In one week in October of that year, there were two runs of unprecedented size, one at Worbarrow Bay on the Purbeck coast, the other further west near Bridport. The run at Worbarrow involved no less than five ships unloading simultaneously and an observer described "a perfect fair at the waterside, some buying of goods and others loading of horses; that there was an army of people, armed and in disguise, as many in number as he thought might be usually at Dorchester fair, and that all the officers in the county were not sufficient to oppose them". In the Bridport run, a great quantity of brandy and salt was brought ashore and "carried off by great numbers of the country people" in full view of the Customs staff.

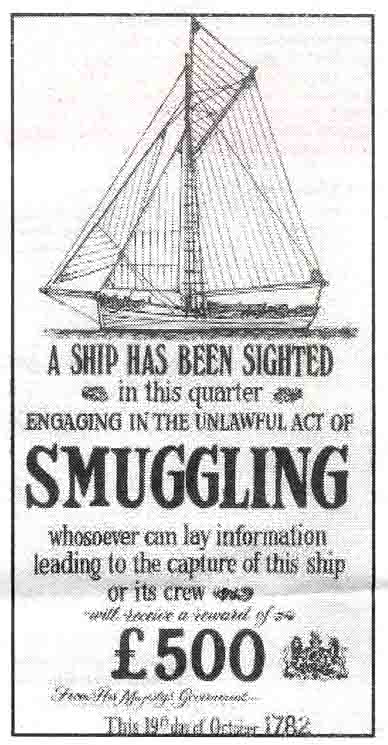

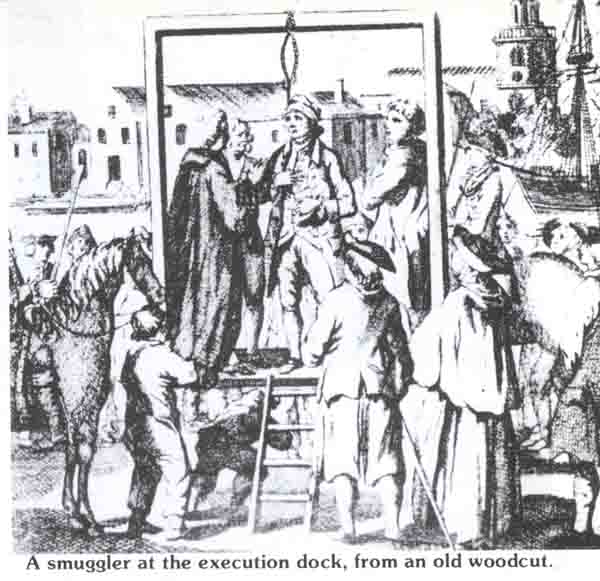

Philip Taylor was not exaggerating when he reported that "the tumultuous and riotous proceedings of the smugglers is not anything abated but daily growing upon us". He went on: "Most of the smuggling trade in this country is now carried on by people in such great numbers, armed and disguised, that the officers, if they meet them, can't possibly oppose them therein, nor do otherwise than search for the goods in suspected places, which by means of the country's favouring the smugglers, very often proves ineffectual and expensive to the officers." But if they did get caught and sentenced, they could be hung!

|

|

Brandy and wine made up the bulk of the contraband cargoes landed in Dorset

between 1716 and the mid-1730s, but many other commodities appear in the lists

from time to time, including rum, coffee, tea, salt, pepper, cocoa beans, vinegar,

cloth, silk handkerchiefs, tobacco, playing cards, foreign

paper and logwood.

"Hovering"

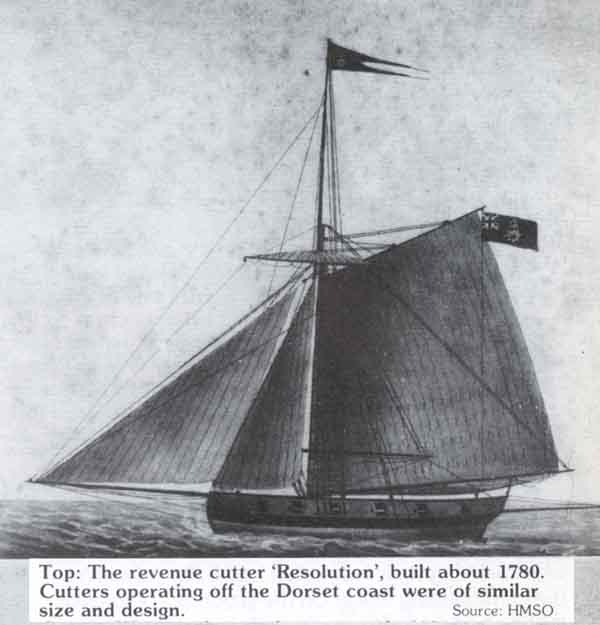

Ships of all sizes, both foreign and English, sometimes hovered off the coast for several days while gangs were organised for an illegal landing, and until the first of several "hovering" acts was passed in 1719 there was nothing the Customs men could do. If questioned by the skipper of a revenue vessel, the captains usually claimed they were bound for some place which was of no concern to the officers, such as the Channel Islands, France or Holland.

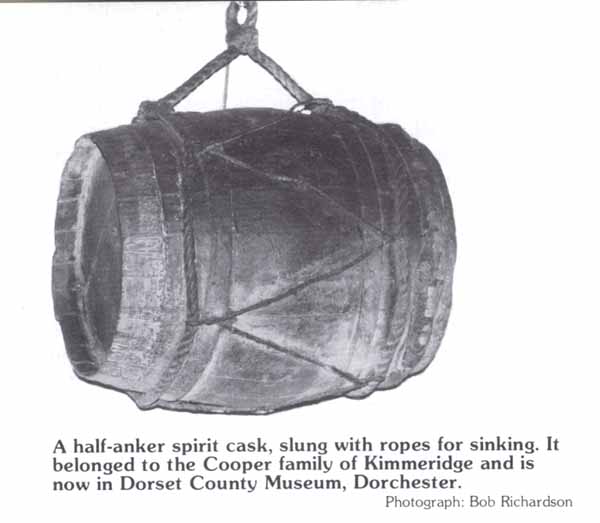

The act made hovering illegal within six miles of the coast and many smugglers now found it safer to bring their goods ashore immediately and, when necessary, hide them among rocks, in hedges and ditches and coastal cottages, or even bury them on the beach. A useful alternative in the case of smuggled wine and spirits was to dump them in the sea and collect them later - a method which was to become standard practice among later generations of smugglers and which became known as "sowing the crop".

In November 1720, some fishermen from Abbotsbury made an unusual catch a mile offshore near Burton Bradstock and sparked off a remarkable chain of events which ended with a question being asked in the House of Commons. The catch consisted of twenty-three ankers of brandy and two barrels of wine, which had been "moored with ropes to stones" and sunk. The casks were brought ashore at Abbotsbury and lodged at the home of the local Excise officer, a man called Whitteridge, but were then "re-seized" by William Bradford, bailiff to the Lord of the Manor, Mr. Thomas Strangways. Bradford kept the wine and spirits under lock and key for several days, claiming that his master was entitled to take them for his own use, as one of his manorial perks.

The young Customs officer at Abbotsbury, Joseph Hardy, was repeatedly ordered by Philip Taylor to retrieve the goods, but when he did so, he was obstructed by a gang of locals and immediately lost them again. Taylor commented sarcastically: "They [Hardy and Whitteridge] being both the most original fools I ever met with or heard of, in the scuffle of taking the goods away I can't find any blow was struck on either side and (it appears) that the heroical officers were directly frighted out of their goods."

Taylor recognised, though, that just about every person in Abbotsbury was an employee of Strangways, and he concluded that the only way to settle the matter was to call in the army, who had been ordered to help the fight against smuggling when requested. Accordingly he sent a message to Lieutenant Carr, commanding officer of Lord Irwin's Regiment of Horse quartered at Dorchester, and on November 16, Quartermaster William Thomson left the county town with Joseph Hardy and eighteen troops. On arriving at Abbotsbury, they found "a great mob of people gathering themselves about them" and Hardy summoned the parish constable and tithingman and asked them to help keep the peace. At the sight of the troops, Bradford the bailiff changed his attitude rather suddenly, handed over the keys and allowed Hardy to recapture the goods in the face of a vociferous but otherwise peaceful crowd.

But this was not the end of the story. Strangways, refusing to accept defeat, later claimed that the casks of wine and brandy were not contraband at all but salvage from a wrecked ship; he also made a complaint to the Secretary at War concerning the involvement of the troops; and he persuaded one of his gentlemen friends to raise the matter in parliament but to no avail.

Methods of smuggling in the second half of the 18th century

Customs records show that in 1764 ships of the East India Company smuggled tea into this country estimated at seven million pounds annually.

Smugglers had by now refined the art of hiding goods and of avoiding duties on their imported goods. Below are some of the methods used:

Tea cases were fitted between the vessel's timbers and were made to resemble the floors of the ship.

18 lbs. of tea could be hidden under the cape or petticoat trouser worn by the fishermen and pilots of the vessels.

Cotton bags made into the shape of the crown of a hat, a cotton waistcoat, and a cotton bustle and thigh pieces carried in all 30lbs. of tea.

Tobacco, another taxed commodity, was valuable contraband. Made into ropes of two strands, it was coiled with the real rope in the lugger, and was even put into a special compartment in casks of imported bones which were used for manufacturing glue.

The wooden fenders slung over the sides of a ship were hollowed out and filled with tobacco.

There were other ways of bringing in extra tobacco without actual smuggling.

As tobacco readily absorbs moisture from the air, it increases in weight in

damp localities. One manufacturer avoided paying too much duty on his cargo

by establishing a series of drying rooms on one of the Channel

Islands. This room was heated to 90 degrees and he despatched large quantities

of leaf tobacco to the depot.

After it had dried out, the tobacco was tightly packed into barrels and then imported to England. He paid the duty on the dried tobacco, thus tobacco weighing 100 lbs. could, by drying, be reduced to 60 lbs.

It was then taken to a factory, unpacked, and exposed to the air, and regained its original weight. A handsome profit was made by the manufacturer. Later, a law was passed imposing duty on tobacco "according to the quantity of moisture contained therein". Since the rate was higher if the tobacco was dried, then there was no point in the tobacco being dry.

Spirits, both brandy and gin, had intriguing journeys into our ports.

Brandy was chiefly imported from France. Excellent cognac was shipped from Roscoff.

Gin, popular with the troops who had taken part in the Dutch wars, was imported

from the Low Countries. Flushing exported gin chiefly to the East Coast.

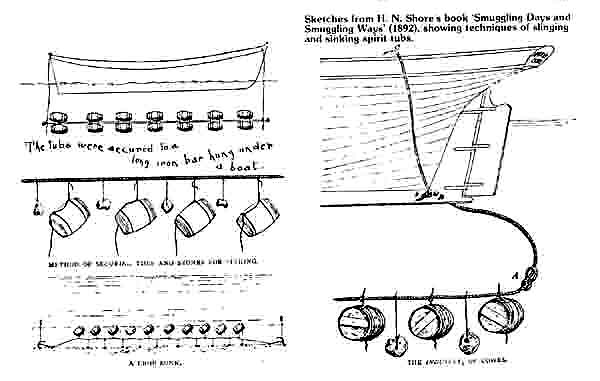

Brandy or gin tubs, roped singly or in pairs and anchored with sinking stones, could be cut off easily and left with markers if Revenue Cutters were in sight.

Tubs of spirits were packed into the hollowed keels of boats, hidden under false bottoms, or fitted into rafts or punts which were floated on a flood tide to persons waiting on the shore.

In his book on Boldre, in the New Forest, Mr. Frank Perkins tells about smugglers at Pitts Deep, Boldre, Hampshire.

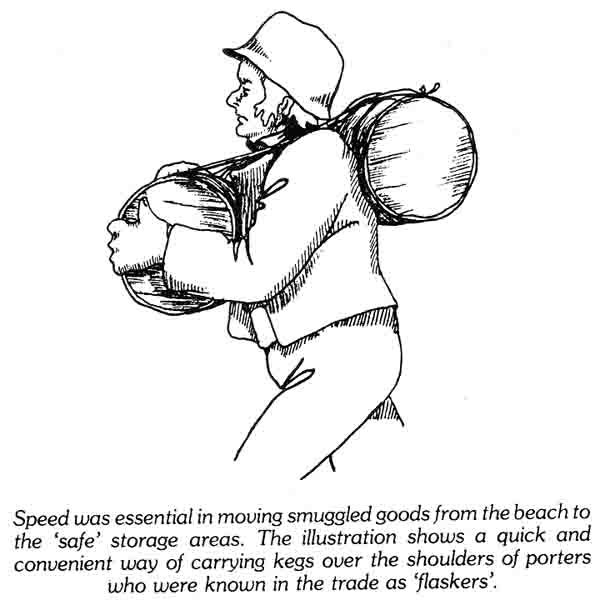

"The kegs of spirits, roped together, were sunk and marked with a float, about one quarter of a mile from the shore, in the Pitts Deep stream, at a spot known as Brandy Hole. The kegs were floated ashore by punts, as by this way it was easier to sink them if a coastguard arrived.

The kegs were carried from the shore by a gang of local men to carts which were waiting a short distance away, but if dangerous for the carts to load up, the kegs were easily slung across the shoulders, generally one in front and two behind. The pay was 2/ 6d. per keg."

Not only were women useful to the smugglers as signallers and carriers of messages from members of the gang to each other, but they actually brought goods in from the shore for them.

The voluminous skirt was a particularly useful fashion, for the women wound yards of silk and lace round their bodies and reached home as a rule quite peacefully with their contraband.

There have been cases, however, when women have, on inspection, been found to have had their petticoats puffed out by bladders filled with spirits.

A report from a Hampshire Chronicle of March 25th 1799 stated that

"A woman of the name of Maclane, residing at Gosport, accustomed to supply the crew of Queen Charlotte with slops went out in a wherry to Spithead, when a sudden squall coming on, the boat sank; the watermen were drowned, but the life of the woman was providentially saved, by being buoyed up with a quantity of bladders, which had been secreted round her for the purpose of smuggling liquor into the ship, until she was picked up by the boat of a transport lying near." A case of being buoyed up by good spirits no doubt!

In a report from the Customs House at Weymouth in 1804, Burton's Hive Beach is mentioned:

"The articles generally smuggled from this part of the coast are chiefly

brandy, rum and geneva, to which may be added a small quantity of wine, tobacco

and salt, the whole from the islands of Guernsey and Alderney, which are imported

in casks containing from four to six gallons each in vessels from ten to thirty

tons burthen in the winter, and in the summer season in boats from three to

eight or nine tons carrying three hundred and fifty casks, which are generally

sunk on rafts till a convenient opportunity offers for taking them up, which

they put into boats and distribute them along the coast at Portland and on the

beach called Chiswell Beach as far west as Burton Hive,

which is about sixteen miles in extent. It then gets into the hands of women

and others, who disperse it in small quantities in the country for five or six

miles round, and what is not got rid of in this manner is conveyed on horses

forty or fifty miles up the country; but when from tempestuous weather the smugglers

cannot sink their goods, they then work to the eastward of that island and sink

and disperse it in like manner.

The places for landing the smuggled goods to the eastward of this place are Jordan Gate, Upton Mills, Ringstead Beach, Mupe, Arish Mill [Mell] and Worbarrow Beach. The three latter are the most noted places. It frequently happens that large vessels carrying from four to six or seven hundred casks land their cargoes at these places, which vessels do not belong to or are known to any in this part of the coast. This they carry off in waggons, carts or on horse, escorted by large gangs of smugglers in defiance to the officers on this station, but goods so brought come not with the calculation we have formed which, from the best information we have been able to collect, and which concurs with our opinion, we suppose may amount to ten thousand casks annually, but none of which we apprehend reaches the metropolis…"

In 1813, the Poole officers provided more details of

the sinking method:

The practice of sinking tubs (as the small casks of spirits were now known) became far more common during the Napoleonic wars, from which we must conclude that the preventive forces had at least become sufficiently effective to force the smugglers to adopt a little more secrecy than had previously been employed. As early as 1804 the Weymouth collector stated that casks were "generally sunk on rafts till a convenient opportunity offers for taking them up", and in 1813 the Poole officers provided more details of the sinking method.

"The manner in which the contraband trade is at present carried on, we learn, is for the importing craft to sink their goods according to a previous arrangement at different and distant places on the coast without the necessity of any communication on the shore. The goods being in a manner secure by being thus sunk, the smuggler, proceeding by land, acquaints the owners of the marks by which they may find their respective goods. The means by which the landing is effected is small open boats, usually employed during the day in fishing, which at night are hauled upon the beach, frequently immediately contiguous to the spot where contraband goods are sunk. These afford considerable facility to the smuggler, who thereby is enabled to suit his own convenience in landing his goods, which (availing himself of opportunity) he may effect in a single hour without previously creating the least suspicion. It therefore is not surprising that small quantities are introduced into the country in spite of every exertion and vigilance of the preventive officers.

The number of casks usually landed in this manner is from twenty to forty and are with inconceivable promptitude conveyed to and concealed in caves (or as they are demanded by the smugglers' sellers) situated in the vicinity of the spot where the landing takes place. These caves or cellars are formed with so much secrecy or ingenuity that their detection amounts almost to a matter of impossibility. They are known to be capable of containing from two to five hundred casks. On the North Shore, where heretofore was a good and principal resort for smugglers, we cannot learn that any goods at all have been worked. Two casks have been taken but these, we apprehend, were part of a quantity sunk to the westward and broke up in a gale of wind."

In his book on Dorset smuggling in the 18th and 19th Century ("Smuggling

in Hampshire & Dorset"), Geoffrey Morley talks of the old Dove

Inn in Burton Bradstock (sadly now closed) which was a depot for contraband.

In 1804, Weymouth Customs believed that casks were sunk on rafts between Portland

and Burton Hive beach.

In 1822 coastguard boatmen William Forward and Timothy Tollerway saw two boats

being rowed towards Burton beach, from which whistling signals came. Three smugglers

were confronted, who ran away, dropping their tubs. There were often fights

between smugglers and coast-guards, and those unlucky enough to be caught and

imprisoned, ended up at Dorchester Gaol (Roger - Guttridge adds that the prison

was known as St Peter's Palace).

However, the war against smuggling becomes more effective in the 19th century

THE YEARS IMMEDIATELY following the Napoleonic wars saw a considerable strengthening of the preventive forces all around the British coast. The clampdown had begun in 1805, with the attempt to eliminate the Channel Islands as a contraband trading centre, and had continued in 1809 when the government, concerned at the help the smugglers were giving the emperor, introduced a new force, the Preventive Waterguard, to support the existing services. It consisted of a large number of cruisers and boats under the command of naval officers, whose duty was to patrol the coastal areas while revenue cruisers sailed further out to sea and riding officers guarded the land.

But it was the ending of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 which brought about the biggest changes. The long-awaited peace led to the demobilisation of three hundred thousand soldiers and sailors, many of whom had no other trade or occupation in which to channel their energies. The Lords Commissioners to the Treasury accurately predicted that "after so long a period of war in every part of Europe, many of the most daring professional men, discharged from their occupation and averse to the daily labour of agricultural or mechanical employment, will be the ready instruments of those desperate persons who have a little capital, and are hardy enough to engage in this [smuggling] traffic".

Although there were more potential smugglers around, there were also more soldiers, sailors and preventive men to combat them. Over the next few years, a whole series of measures were taken to increase the numbers of those employed in the prevention of smuggling and to improve co-operation between them. The Waterguard was reorganised into thirty-one districts, each under the command of a naval officer or a former revenue cruiser commander, and these districts were subdivided into one hundred and fifty-one stations each manned by a chief officer, chief boatman and boatmen. Inspecting officers were appointed to visit both Waterguard and riding officers and combined operations were arranged between the various lines of defence to improve efficiency. Naval vessels and troops of soldiers were also drafted in to aid the struggle.

The preventive service

The preventive service

The coasts of Kent and Sussex were given special protection in 1817 with the establishment of the coast blockade, but this was not extended as far as Dorset. However, in 1822 the preventive services were given a further overhaul. The Waterguard, revenue cruisers and riding officers were amalgamated under the control of the Board of Customs and given a new collective name, the Coastguard. Terraces of cottages to house the Coastguard officers were built at strategic spots all along the coast, at Lyme Regis, Chideock, Burton Bradstock, Bridport, Abbotsbury, Kimmeridge, St. Albans Head, Swanage, Studland, Brownsea and Bourne Bottom.

In the 1820's

Opening page of instructions to the Coastguard, 1829. Source: HMSO (The instructions are quite clear!)

"General Instructions

All officers and Persons employed in the Coast Guard, are to bear in mind that the sole object of their appointment is the Protection of the Revenue: and that their utmost endeavours are therefore to be used to prevent the landing of uncustomed goods, and to seize all persons, vessels, boats, cattle, and carriages, in any way employed in Smuggling and all goods liable to be forfeited by law.

Every Person in the Coast Guard is to consider it his first and most important object to secure the person of the Smuggler; and the reward granted for each smuggler convicted, or the share of the penalty recovered from him, will be paid (on the Certificate of the Inspecting Commander) to the person or persons by whom the smuggler is absolutely taken and secured, and not to the crew in general.

Every Officer and Person employed in the Coast Guard is hereby strictly charged not to do, consent to, abet, or conceal any act or thing wherein or….."

In the 1870s - Bonfire signals

Charles Warne, in "Ancient Dorset", 1872, states that an Act of Parliament made the lighting of fires along the coast as a signal to homeward bound smuggling craft, was a punishable offence and Thomas Hardy, in "The Distracted Preacher", has Lizzy Newberry at new moon light a bush on the cliff, to warn the smugglers that the "Preventive-men knew where the tubs were to be landed". She expected they would then sink the tubs, strung to a stray-line at sea, to be later raised by a "creeper", a grapnel.

Stories of some less well known local smugglers

The most persistently troublesome centres in the Lyme Custom House area were Beer in Devon, and Chideock and Burton Bradstock in Dorset. At Chideock and Seatown, practically every family was involved in the trade, with the Bartletts, Farwells, Oxenburys and Orchards leading the way. A nineteenth century vicar of Chideock, the Rev. C. V. Goddard, wrote in his notes on smuggling:

"The fishing interest seems to have slipped away with the dwellings at Seatown. Some say the fish have left the coast but others (with whom I agree) that in the old days the fishermen lived more by smuggling than by fishing. They were a hardy lot, and the son of one of them, himself engaged in the trade as a youth, recalls the smuggling yarns that he, as a little boy, used to hear them tell and the adventures in which he later took part. There were wild rushes to the West Rocks (beneath Golden Cap) when a boat-load of spirits was being rowed ashore from a ship lying out at sea, each man readily shouldering his share of the load - two small kegs - and scrambling off as fast as his legs would carry him. He would find his own way inland to a safe retreat. Cranborne Chase, being a wild, uninhabited district, and the central moors of Dorset, were favourite hiding places."

There was a rumpus on the beach at Seatown in 1824, when Chideock coastguards Joseph Davy and John Rigler tried to seize a smuggling vessel, the Fancy, from Seaton in Devon as she was setting off from the beach. Davy managed to make a technical seizure by marking the boat with a broad arrow but was then set upon by Robert and William Foss, two of the smugglers. Robert Foss held up his fist to Davy and shouted: "Damn your eyes! This shall be the worst day's work you ever did in your life." William Foss then grabbed Davy by the collar, demanded to know what business he had in seizing the boat and held him until a team of horses, which the officer wanted to use to drag the boat back up the beach, had been removed from the scene.

The mill at Chideock had a secret room under the floor of miller James Gerrard's living quarters. It was discovered by the village riding officer, Samuel Dawson, when he searched the premises in 1820, and there he found two casks of brandy and two of geneva. Gerrard was not the most considerate of millers and tried to put the blame on his servant boy, Samuel Long alias Dido. He claimed Dido was "in the habit of going down to the beach to fetch tubs continually", and that a day or two earlier, he had said to him: "That's a really good place to hide tubs, master. The officers will never find them there". Gerrard's story fell flat, however, when it was learned that upon hearing of the discovery, his brother, Anthony, who also lived in the house, "went away into the country" and disappeared for a while.

Dawson and Excise man Samuel Hall discovered another secret room at nearby

Whitchurch Canonicorum two years later. They were searching the home of a suspected

tub-carrier, John Wakely, and noticed a new partition in one of the upper rooms.

Wakely insisted it was just a very thick wall and proceeded to leave the house

with his wife and sons without further ado. Left to search the building in their

own good time, the officers eventually found a trapdoor leading from a workshop

below the stairs. In the hollow compartment were four casks of brandy

and three of geneva.

If there was any smuggling at all in south-west Dorset, the preventive officers could be sure to find it at Burton Bradstock for this had long been a noted contraband centre and official fears of a great revival in the trade there after the peace in 1815 were well-judged. Here and at Swyre, two or three miles to the east, the Northovers had a finger in every tub and provided regular employment for the keeper of Dorchester Gaol.

There was a violent clash on the beach at Burton in December 1822 and inevitably at least one Northover, James the younger, of Litton Cheney, was involved. He was supposed to have struck an officer with a stone but was later acquitted at Dorchester Assizes. The incident began between nine and ten in the evening, when Coastguard boatmen saw two boats being rowed towards the shore and heard whistling, which they took to be a signal to someone on the shore. Three or four men came down the beach and one was heard to say: "Go further east." The coastguards, William Forward and Timothy Tollerway, crept along the beach and came face to face with three smugglers, who dropped the tubs from their backs and ran off. Their comrades were less cooperative. Leaving Tollerway to look after the discarded goods, Forward crept on and seized another dozen or so tubs, then fired his pistol to summon assistance. At this, the remaining smugglers converged on Forward, held his arms to prevent his firing again and dragged him to the water's edge. He called for help and Tollerway fired his pistol, but before other officers arrived, fighting broke out and several smugglers were wounded, though they still managed to escape with all but two of the tubs. Only Northover and sixty-four-year-old William Churchill, of Puncknowle, were detained and the latter spent fourteen months in Dorchester prison for smuggling and assault.

The Northovers of Swyre and Litton Cheney were anxious to maintain the traditions established by their forefathers. They and other smugglers threatened coastguards from Bridport with sticks and bludgeons when a landing at Swyre was interrupted in 1825. James Northover threatened to kill the chief boatman if he came any closer, but the officer was undaunted and gave chase. One smuggler escaped by jumping over a hedge, the others by scrambling over a stone wall. The officer was about to climb the wall himself when Joseph Northover let fly with his fists and delivered a blow which "rendered him insensible for a short time". The smugglers got away but John Thorne alias Thorner was later imprisoned for obstructing the officers. The Northovers were convicted but not imprisoned, although James twice visited the county gaol and was impressed into the navy for another offence in 1827.

The 'last' smuggling run.

The notes of the Rev. Goddard date the last run at Chideock as late as 1882. It was led by the sixty-nine-year-old veteran smuggler Sam Bartlett and began with the customary exchange of signals with the French vessel hovering off the coast. All was well as the Chideock smugglers put off from Seatown in a boat to collect their tubs. But the transfer took longer than expected and they knew the Coastguard patrol would now be in position. After delaying awhile, the boat approached the shore at Eype's Mouth, where other smugglers were waiting. There was a mishap, with one man falling down the cliff and colliding with another, scarring him for life. A few tubs were landed but then the patrol was spotted and the alarm raised. The smugglers decided to open a tub rather than risk having it seized, but one of them drank so much that he died an extremely merry death. The boat put to sea again and sank the tubs off Seatown.

Months passed before another opportunity presented itself. This time an attempt was made at Burton Bradstock, but the surf was running high and no boat could go in or out. A few tubs were landed, and removed through a potato field by waggon, but half the original cargo remained at sea. Another landing was attempted below Thorncombe Beacon, but the preventive men were alerted, the boat's tackle got hitched and the tubs were dumped back in the sea once more.

Some days passed before the tubs were raised again. This time the chosen spot was the sluices of Bridport Harbour. A few more tubs were put ashore but then the preventives intervened and once more the boat put to sea. Eventually it made its way to Abbotsbury where, at last, the final part of the cargo was landed.

So ended Chideock's last run and, almost certainly, the last significant run of good French brandy into Dorset. It had taken six months, three sinkings and five attempts at landing. Earlier generations of smugglers must have been writhing in their graves in shame as the last of their breed dithered and dallied and ferried their tubs hither and thither, desperate to avoid contact with the revenue men. "What matter if the gobblers were about? Could they not be bribed with a keg or two, or beaten into submission, or shot out of existence?"

Ghosts in Burton Bradstock?

It has been suggested that local ghost stories were encouraged by smugglers as a cover up for nocturnal activities, for example, a headless dog which crosses the road at Catholes. Also, a coach with four headless horsemen and horses between Burton Bradstock and Shipton Gorge at mid-night. Could it be that these were smugglers stories to keep people off the roads at night, or are there really ghosts in Burton Bradstock?

There was, until 1912, a coastguard station in the hamlet of Seatown to the

west of Bridport Harbour. The old people of the area have said that some

old smugglers' cottages fell into the sea due to the slipping away of the coast.

The fishermen-smugglers who lived there were 'a hardy lot' they say.

From West Bay, the chief route of the free-traders would appear to have

been "through Powerstock and Hooke, then over Toller Down".

At Toller Down there was an inn much frequented by the smugglers called The

Jolly Sailor. The ruins of the inn may still be there.

Poem on Burton Bradstock:

William Crowe, Rector of Stoke Abbott from 1782-1788, wrote a poem, "Lewes-Dun Hill" which refers to Burton Bradstock.:

"These, Burton, and thy lofty cliff, where oft

The nightly blaze is kindled; further seen ...

The stealth - approaching vessel, homeward bound

From Havre or the Norman Isles, with freight

of wines and hotter drinks, the trash of France,

Forbidden merchandise"

THE MAIN SMUGGLING CENTRES IN LYME BAY

The failings and corruption of the Weymouth officials

had historic origins: even in the early 16th century the ironically named

George Whelplay had difficulty making any progress against concerted local

support for smuggling. He was originally a London Haberdasher, but he contrived

to make considerable sums of money by becoming a public informer. As such

he was entitled to half of the fine levied on people caught as a result of

his actions. Since smuggling amounted to a national pastime, this did not

make him a popular man. He overstepped the mark in 1538, incurring the wrath

not only of the crooked merchants, but also of the customs officials themselves.

Weymouth and Portland

However, it has to be said that the witness was 'much in

Liquor' when reporting the drowning. In another incident a customs house officer

was murdered at the 16th century Black Dog Inn in the town, while trying to

arrest a smuggler who had taken refuge there.

The battle between the revenue men and smugglers wasn't

entirely one-sided, as a tombstone on the outskirts of Weymouth testifies.

In its shadow lies the body of a smuggler cut down by a shot from a smuggling

schooner. His bitter wife had this epitaph carved on the stone [99]:

Of life bereft, by fell design

I mingle with my fellow clay

On God's Protection I recline

To save me on the Judgment Day

There shall each blood-stained soul appear

Repent, all, ere it be too late

Or else a dreadful doom you'll hear,

For God will soon avenge my fate.

Chesil Beach

Chickerell and Moonfleet

Abbotsbury

Burton Bradstock

Chideock

Lyme Regis

[105] Treves